For the last six months or so, I have taken on a reading mission of sorts – what I so imaginatively have titled “The Moviebook Project”…

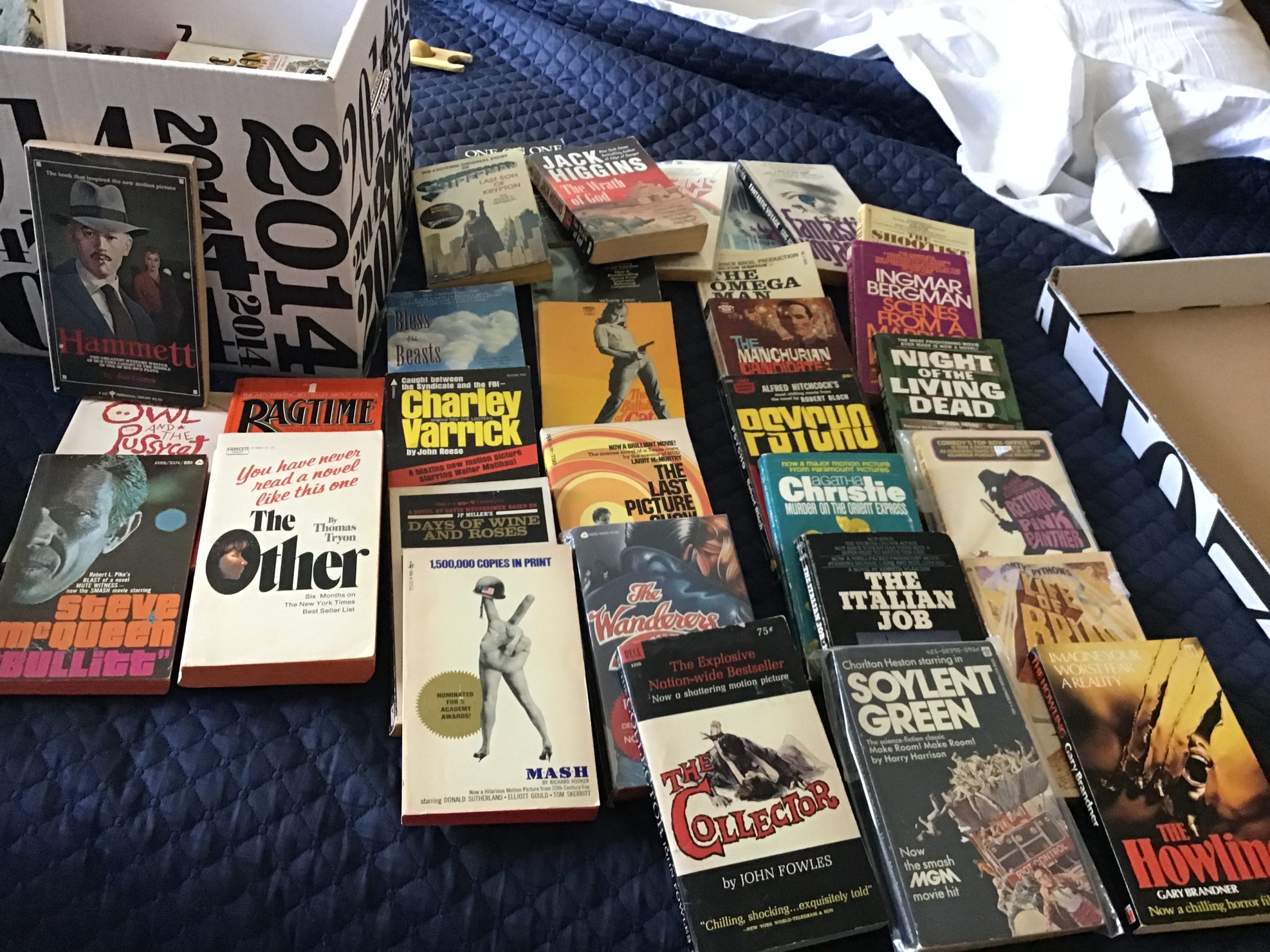

The mission that I chose to accept is to read old movie tie-in paperbacks from the 1970’s and ‘80’s – both classic source novels and low-brow novelizations – and then watch the film version to study how it was adapted and how well it worked or didn’t work in both mediums.

Basically, I’m trying to relearn the architecture of storytelling.

And okay, yes, it also happens to simultaneously feed three of my favorite fetishes – an obsession with the movies I grew up on (what film critics often call “the last golden era of Hollywood”), a collecting jones for vintage paperbacks in general, and my overall weakness for any sort of nostalgia.

So, it has been half academic study, half time-travel redemption.

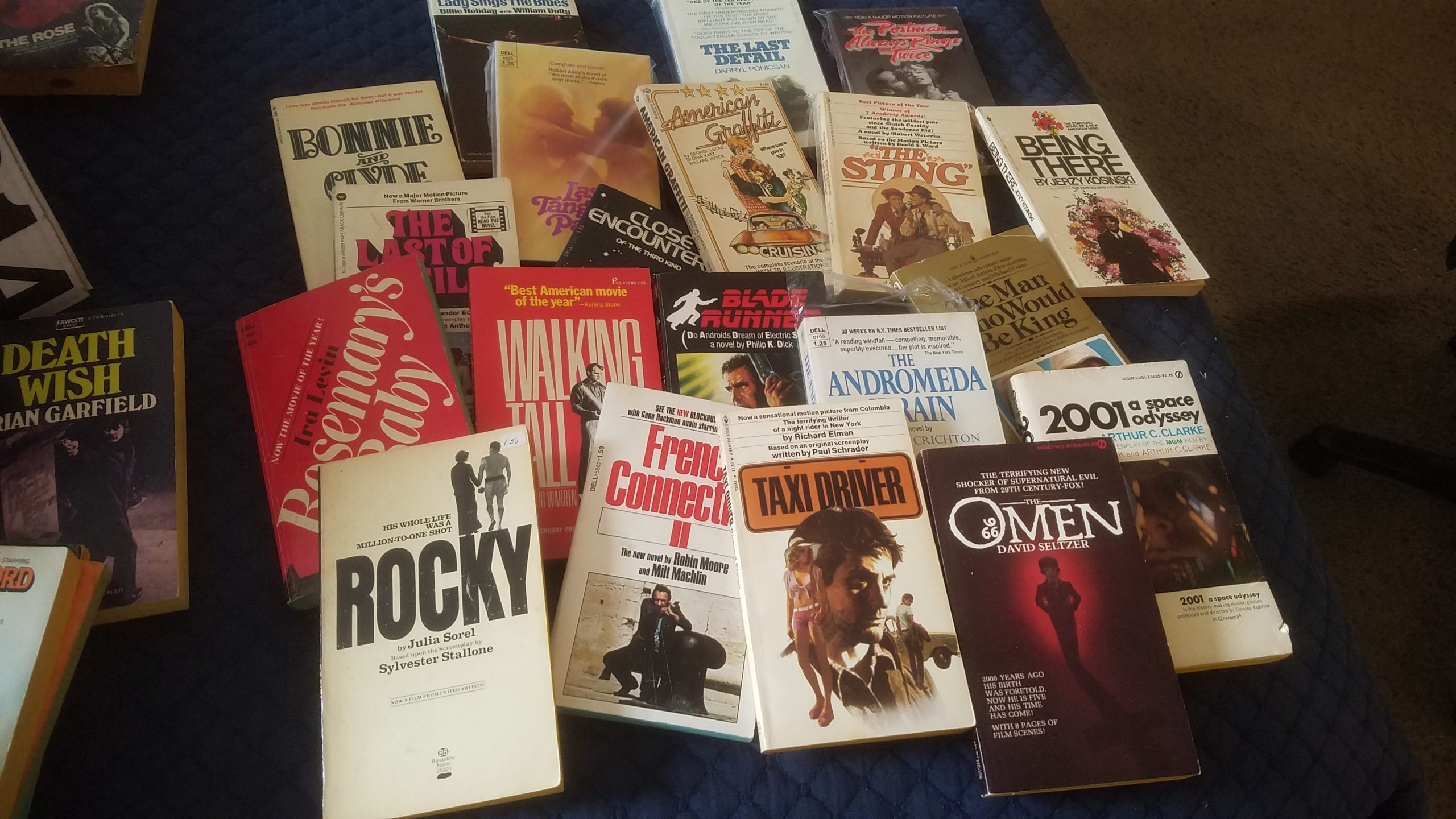

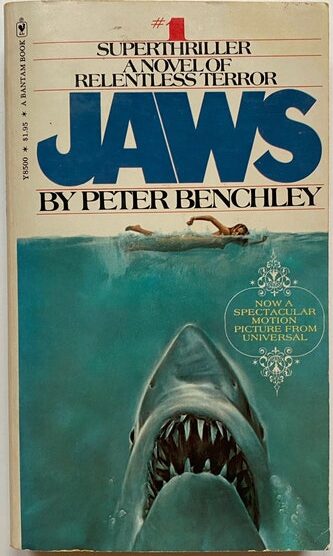

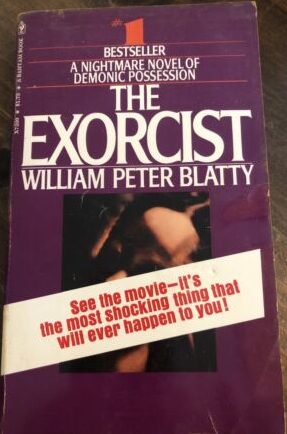

With classic novels/movies (like The Godfather, The Exorcist, Jaws), I really could not believe that as a young movie geek I had so often skipped reading the source material – that I didn’t have the artistic curiosity or, more likely, was just too damn lazy. So the unofficial rule for the project became that I had to find the very specific and iconic paperback versions I would and SHOULD have read back in the day. No glossy anniversary edition with “A New Forward By—“. I wanted to feel like I was browsing an old drugstore spin rack; pulling out the authentic original with all the same tactile sensations four decades later – even if it meant reading cramped type on an age-tanned page.

It may seem like a silly requirement, and it probably is, but it made the hunt on Ebay that much more difficult, and therefore more fun.

With the novelizations, the tricky part was finding decent copies at all. Many of them are much more expensive than the famous novels just by the mere fact of their obscurity, and in some cases, downright rarity.

To be honest, when I was younger I had zero interest in reading novelizations. I riffled through them in the bookstore but never bought them. The idea of trying to experience on the page what had already been filmed seemed pointless to me. I figured they were written by “hacks” and could only be clunky and obvious.

And some novelizations – many even – DO fall into that category.

But what I didn’t appreciate at the time is that these assignments were often given to talented novelists who, through no fault of their own, had just never broken out into mainstream success. These were hard-working writers who needed the paycheck, yes, but who couldn’t “phone it in” even if they wanted to because it was too important. Besides their natural love for good storytelling, they also wanted to take advantage of all those eyeballs on their work and steer readers to their other, more personal books.

Given a bit of a fool’s errand, they welcomed the challenge of somehow making the story their own and showing off their talent in the process.

Time has humbled me (and how!), so I have genuine respect for all those poor ink-stained wretches now.

So what novels and novelizations have I read so far?

- True Grit

- Klute

- Straw Dogs

- Summer Of ’42

- The Hot Rock

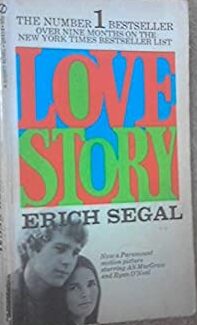

- Love Story

- The Godfather

- The Exorcist

- Jaws

- Paper Moon (Addie Pray)

- True Grit

- Network

- American Gigolo

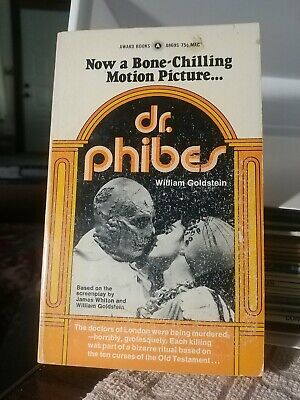

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes

- The Stepford Wives

- Midnight Cowboy

- The Friends Of Eddie Coyle

- Marathon Man

- Duel

- Time After Time

- Alien

- The Thing

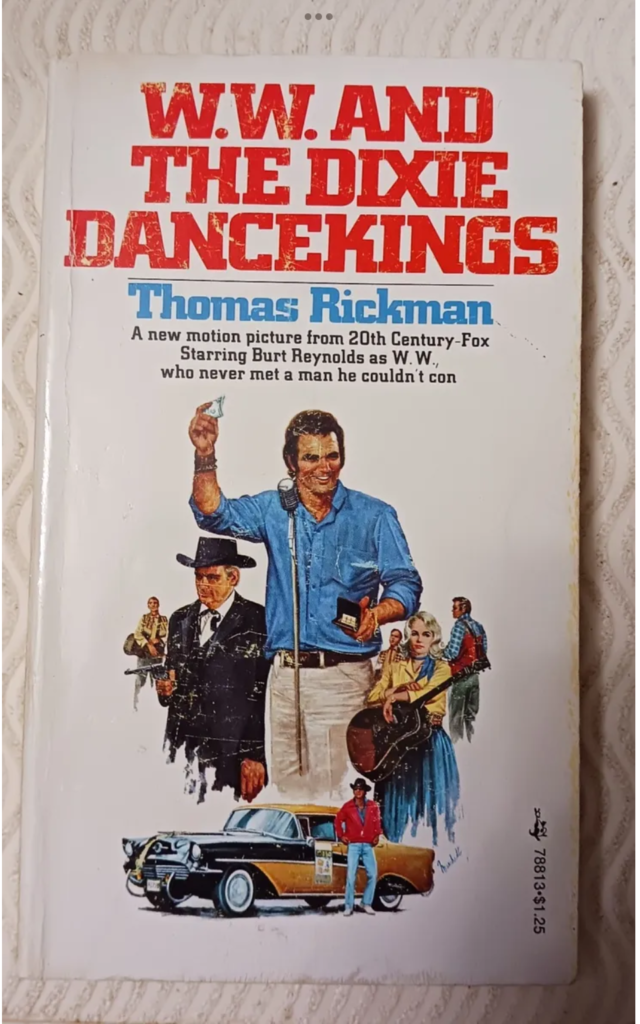

- WW And The Dixie Dancekings

- Candy

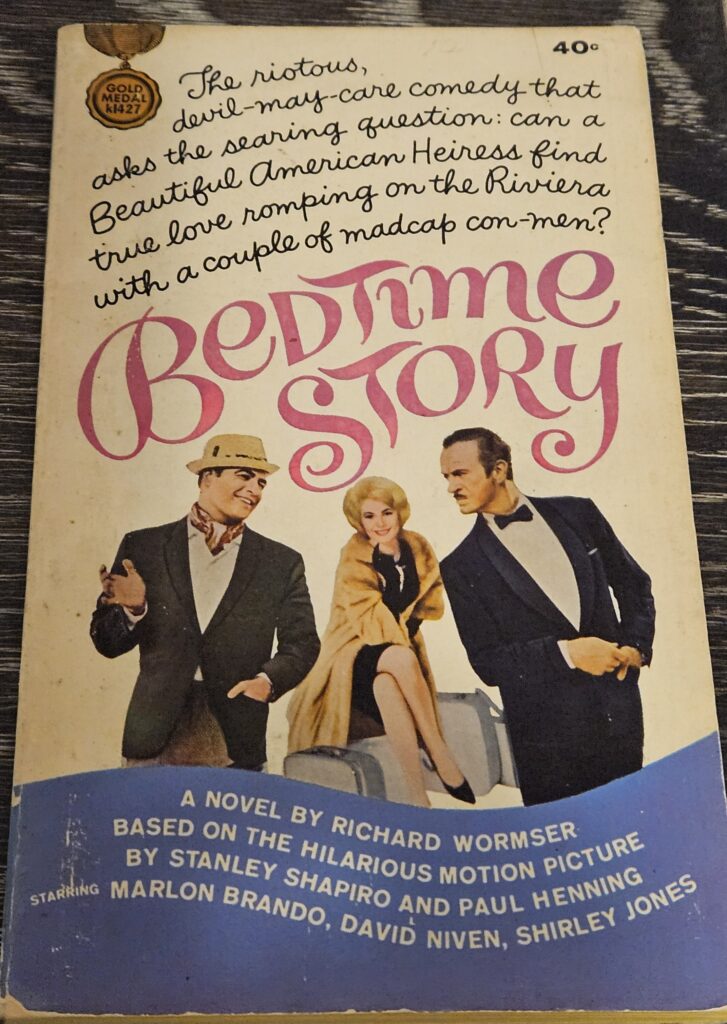

- Bedtime Story

- That Cold Day In The Park

- Last Summer

- The Front

- Save The Tiger

- A New Leaf

- Deliverance

- They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

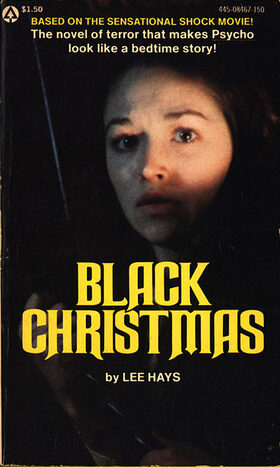

- Black Christmas

- Inserts

- Oh, God

- Harry & Tonto

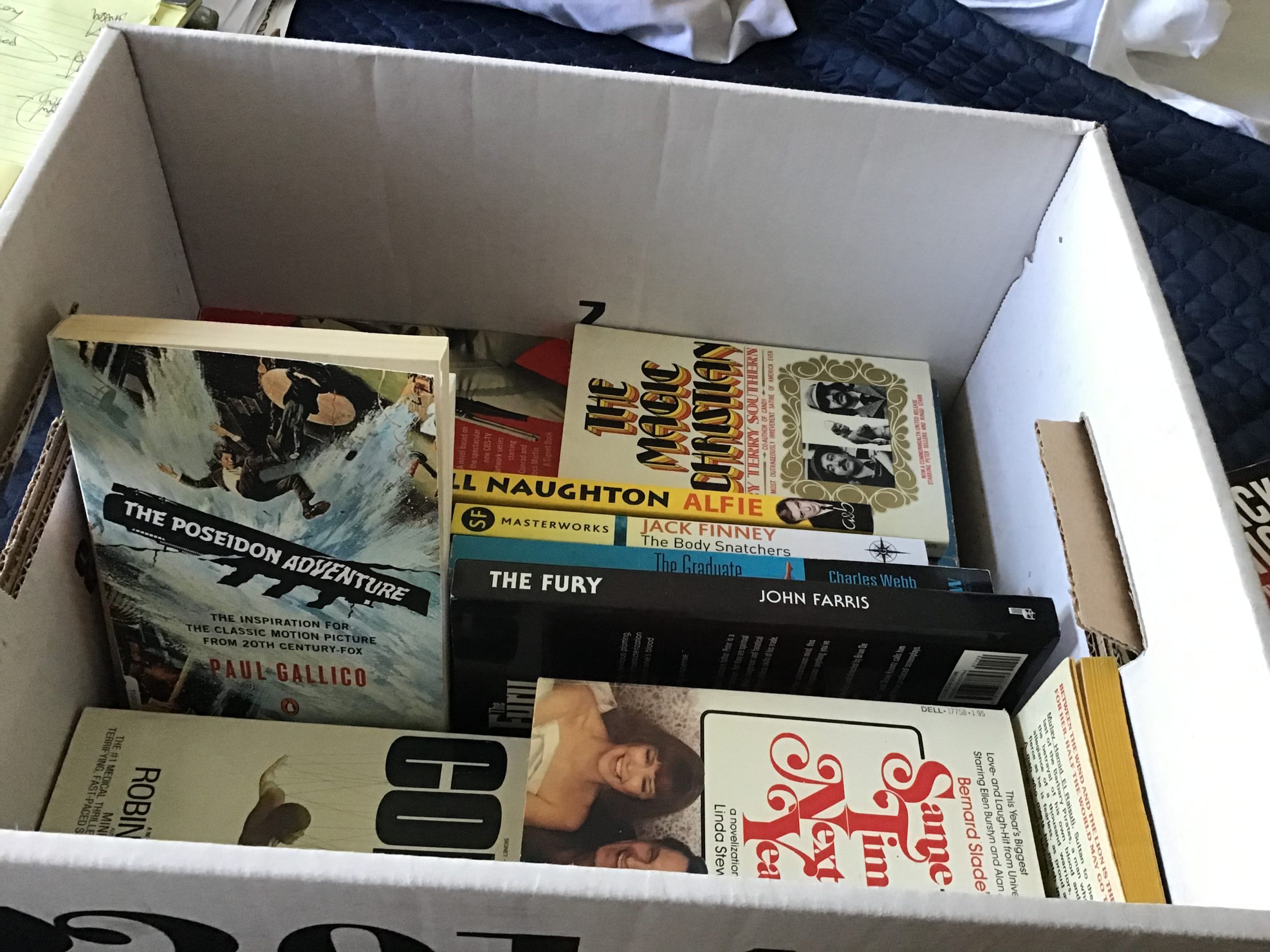

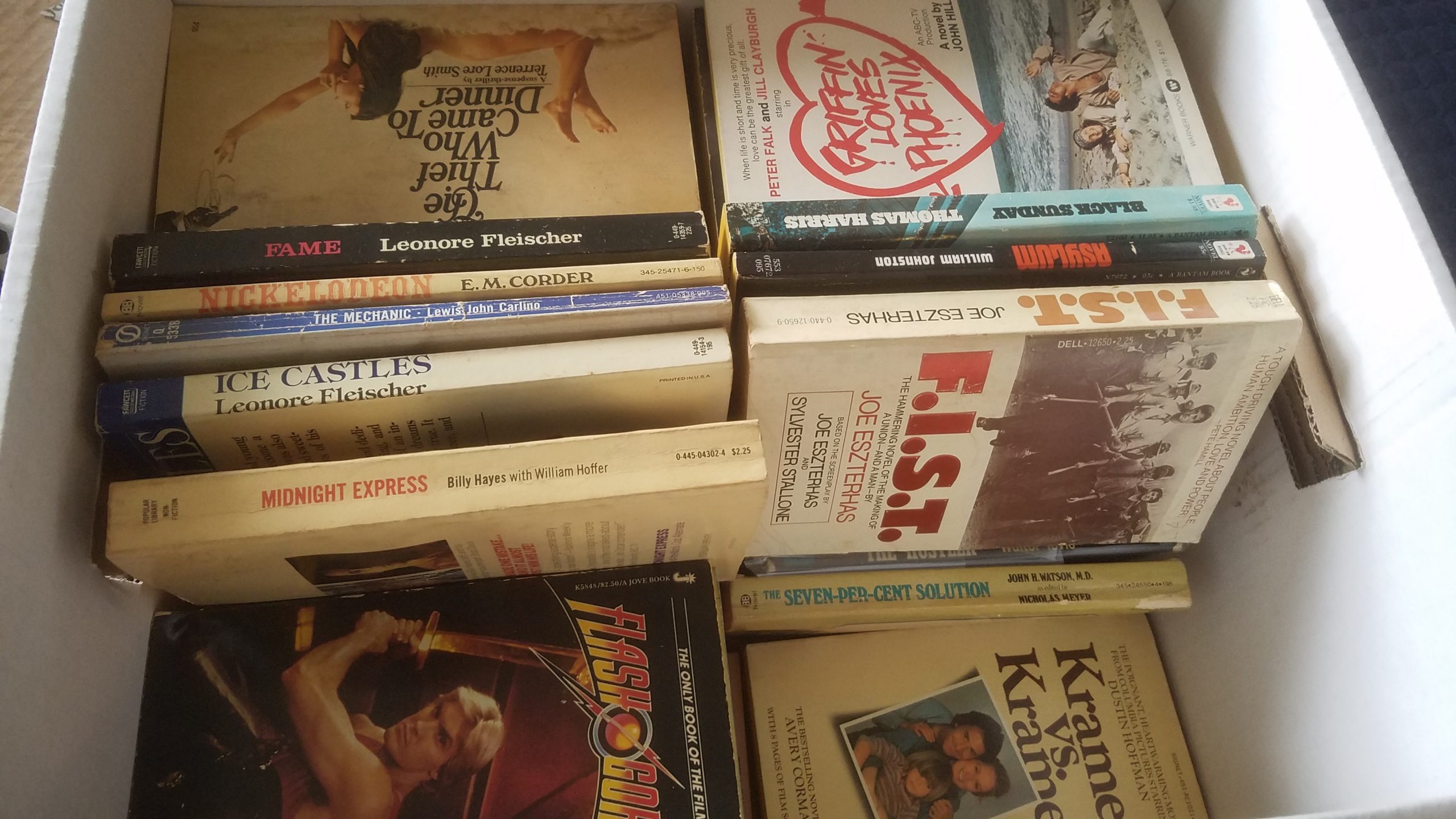

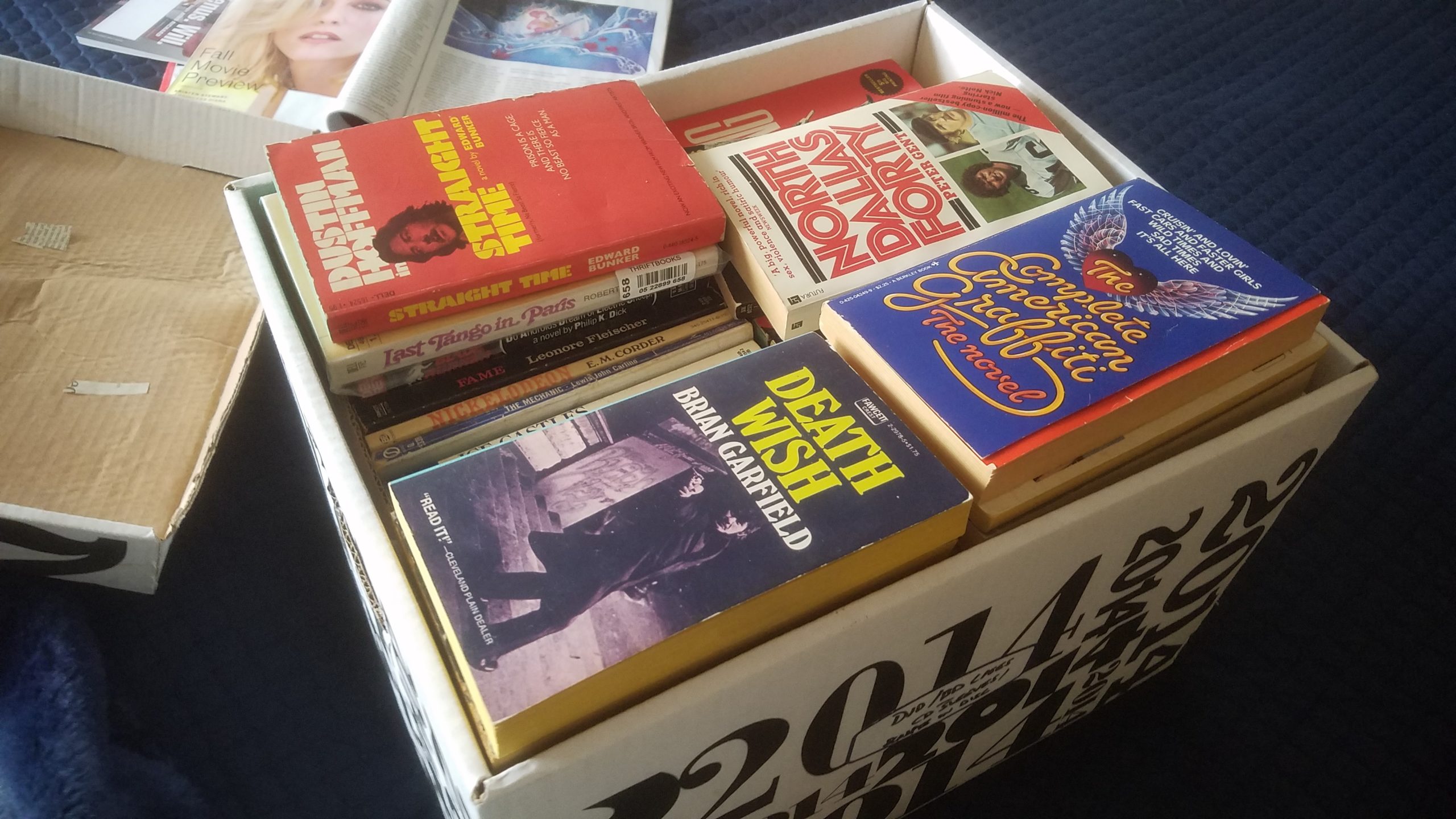

And, as you can see from the photos, I have many big-name titles (almost 200) still to go! As I make my way through the list, I will post updates, quick reactions, and probably a few in-depth reviews on the most interesting ones…

* * *

A quick summary of my thoughts so far:

THE SOURCE NOVELS

The aforementioned legendary titles, Jaws, The Exorcist, and The Godfather, lived up to their reputations and did not disappoint. Yes, they were pulpy potboilers whose sensationalist material was somewhat elevated by Spielberg, Friedkin, and Coppola respectively, but all three laid out very solid, specific templates for the resulting films. It is not difficult to see how they became bestsellers to begin with or why Hollywood snapped them up.

Love Story really surprised me. I find the movie cringingly mawkish and dated, but the novel is slim, spare, and evokes genuine feeling.

Other titles ranged from very good (Deliverance, Summer of ’42, Oh God!, Marathon Man, The Stepford Wives) to pretty good (Straw Dogs, Save The Tiger, The Hot Rock) to only fair at best (Midnight Cowboy).

BUT FOUR NOVELS absolutely blew me away!

Despite their marginalized status as “genre fiction”, I have no problem at all calling them modern classics:

True Grit by Charles Portis. Pure literary gold. Stands the test of time as much as, and, in my opinion, is the equal of Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. It inspired two great movies in very different eras and styles, and is still better than both.

Paper Moon (Original title: Addie Pray) by Joe David Brown. Pure literary silver? Similar in style and tone to Portis’ book, narrated by another young female protagonist in a hilariously colorful Southern vernacular, it has more significant differences from its great film counterpart (screenplay by Alvin Sargent), but is still pure reading joy from cover to cover.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? by Horace McCoy. Written in the lean style of a hard-boiled crime novel, yes, but also a searing expose of life during The Great Depression. Packs a powerful punch.

The Friends Of Eddie Coyle by George V. Higgins. A gritty, messy, but always human, and very authentic look at the dealings of a group of low-level Boston hoods. Elmore Leonard called it the greatest crime novel ever written. He should know. And after reading it, I can’t imagine anyone arguing with him. It’s great stuff. Which makes it even more disappointing that the 1972 film directed by Peter Yates (Bullitt), starring Robert Mitchum no less, is such a damp squib. What a waste! But as Stephen King often says, the book is still there on the shelf…

All four of these books are MUST READS!

WORST SOURCE NOVEL

The Abominable Dr. Phibes by William Goldstein.

This book contained some of the worst published writing I have ever read in my lifetime – it somehow manages to be amateurish and pretentious at the same time. It was so impenetrable I couldn’t even finish it. After the success of the film, Goldstein wrote a handful of sequels…which almost as a strict bylaw of physics would have to be better than the original. Just god-awful.

Candy and Time After Time – the latter NOT written by filmmaker/author Nicholas Meyer – were also complete messes on the page, but at least were coherent enough to finish. They were Tolstoy next to Dr. Phibes.

BEST NOVELIZATION

Bedtime Story by Richard Wormser.

I broke my 1970’s theme by including this mostly-forgotten comedy from 1964 starring Marlon Brando, David Niven, and Shirley Jones. A silly, sexy farce about two con men in the south of France battling over a rich American widow, people know its more financially successful remake, 1988’s Dirty Rotten Scoundrels with Steve Martin and Michael Caine. I prefer the original.

Of course, when I went to read the novelization I wasn’t expecting much at all, but RICHARD WORMSER just happened to be one of those talented jobbing writers I mentioned earlier who could never give any less than his best and he was clearly having a ball with this one. He manages to improve on the film by changing the narrative point-of-view with each chapter, giving each character their own opinionated say, which really adds to the fun. And if you love stories about the confidence game he gives a master class in the tricks of the trade. It is witty, clever, and actually had me laughing out load.

If you can find a copy on Ebay I highly recommend you check it out. It won’t be my used copy though – I’m holding on to mine.

This was such a joyful surprise I did in fact seek out Wormser’s other books. He wrote a lot of pulp detective stories and Westerns that can still be found. He never became a big name (his autobiography is sadly entitled “How To Become A Complete Non-Entity”), but 6 decades later his craft shines.

Runner-Up: W.W. and The Dixie Dancekings by Thomas Rickman.

Much of what I just said also applies to this charming little comedy about a bank-robbing rogue (Burt Reynolds, natch) who cons his way into managing a Country-Western group in the 1950’s. This is a much sought-after title ever since Quentin Tarantino mentioned it publicly as a favorite of his (and despite the fact most of his fans have never seen and would probably just shrug at the low-key film) and as much I generally hate to agree with him, he is right about this one.

WORST NOVELIZATION

Black Christmas by Lee Hays

The movie is one of my favorite horror films and the paperback is so hard-to-find I could only read a PDF uploaded by a fan online. Any thrill I felt at finally (sort of) getting my hands on it quickly dissipated when I saw what a slipshod job it was. It feels like an assignment that a student on a coffee-fueled bender knocked out the night before his deadline. Given the B-movie standards of 1974, I’m sure that’s pretty much what it was. It is dull, rife with errors, and does not even attempt to add context or depth to the story or characters. In fact, it only muddies the mystery killer’s motivations – the most interesting part of the film!

Lee Hays went on to write other novelizations and they may be good, but this one is the most cursory excuse, exemplifies the worst, of the movie tie-in book.

I finished it, but hated myself all the way.

* * *

Anyway…

More to come on this project and what I learn along the way.

Watch this, uhm, moviebookspace.